Circadian Amplitude and the Future of Continuous Health Monitoring

Jonathan Moustakis

MD, CTO of Lume Health

Olivia Walch

PhD, CEO of Arcascope

3 min read

December 11, 2025

When I talk to shift workers, they often say things like: I feel so flat all the time. Or: I can’t seem to stay asleep, but I can fall asleep any time. Or: sorry I missed our call, I fell asleep.

At which I usually lean back in my chair and think, Ah, yes, of course. Reduced circadian amplitude. Then we rebook the call.

Amplitude is a pet topic of mine in the circadian science world, because I think we (as a field) focus too much on making rhythms earlier or later and not enough on making them stronger. We tell people to get light first thing in the morning, which might be right for them… unless they’re already chronically waking up earlier than they want to, like many older people are. We emphasize—and overemphasize—the dangers of light 30 minutes before bed while selectively tuning out the fact that 30 minutes before bed is just 3% of a 16 hour waking day.

There’s a whole lot more day in your day, and light matters for all of it! And what getting very bright days (across the whole day) and very dark nights (across the whole night) gets you is increased circadian amplitude.

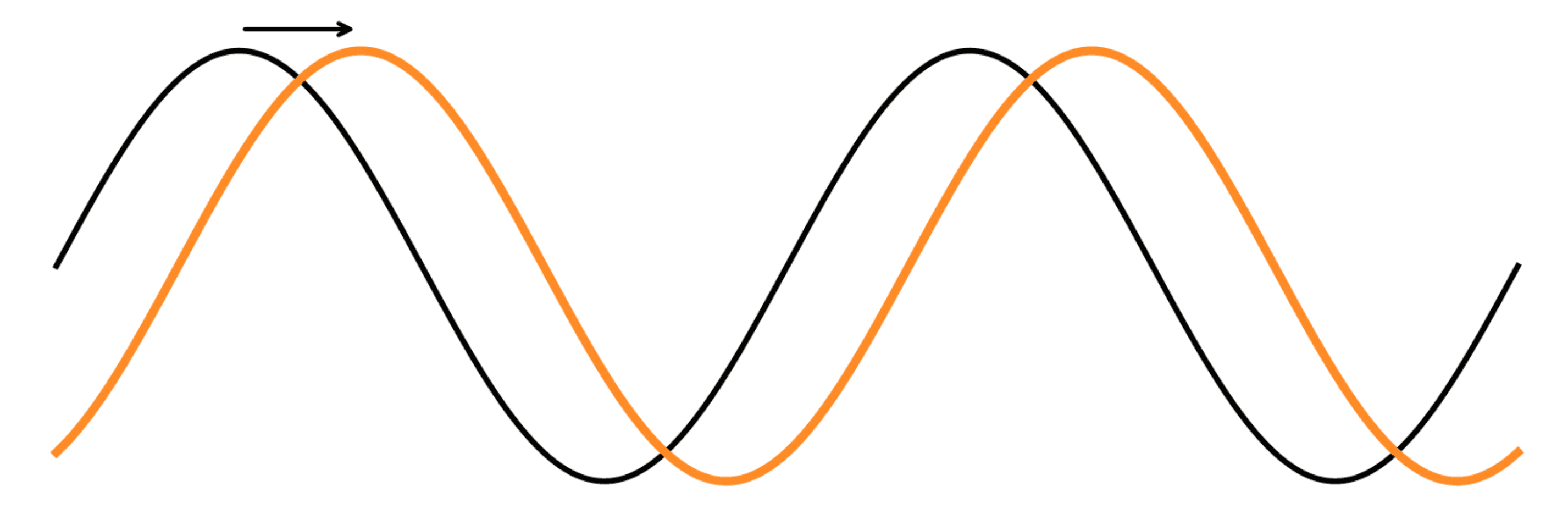

Let’s get on the same page really quick. Circadian rhythms, being rhythms, can be described by where they are horizontally in time, which you can think of as their phase or phase offset…

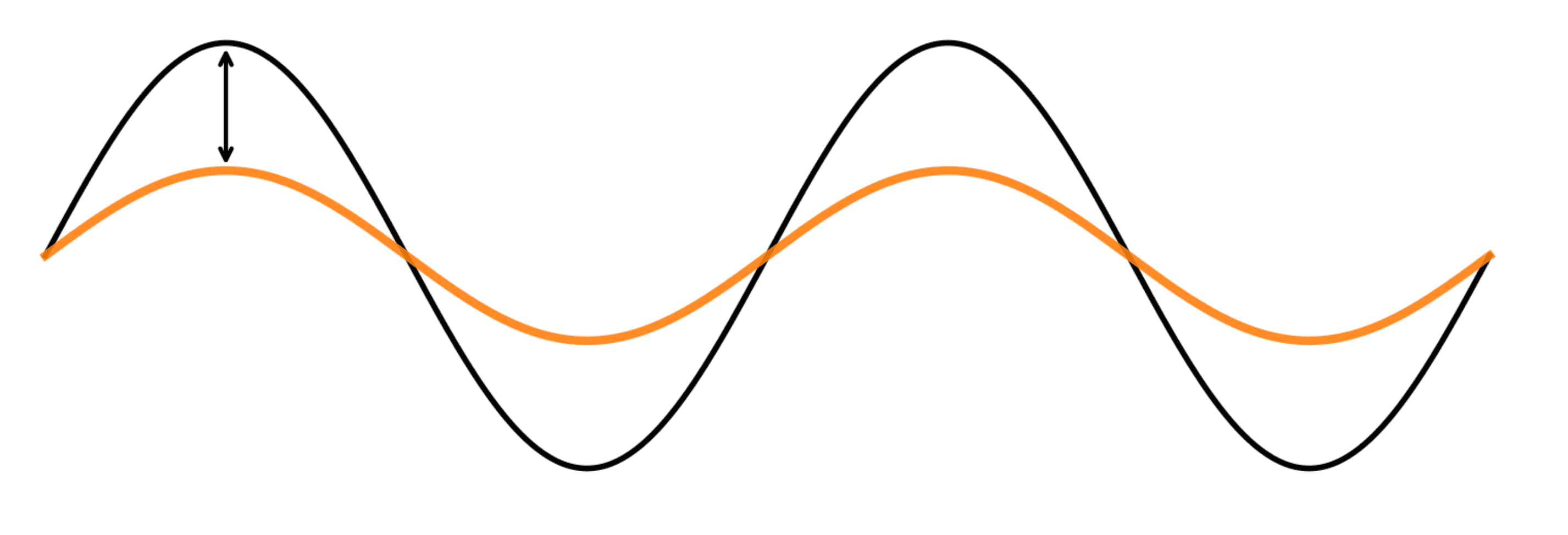

…and also how much they rise and fall vertically over the day, which we typically call amplitude.

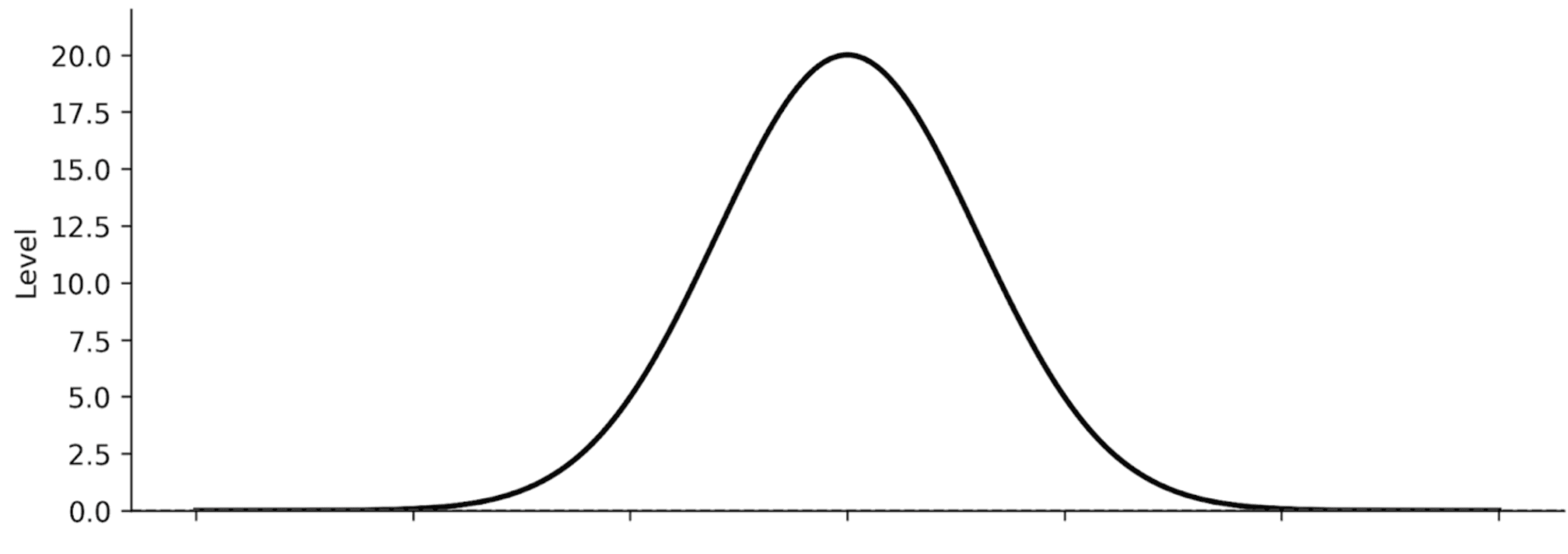

There’s also how high or low their midline is, which is usually called the mesor:

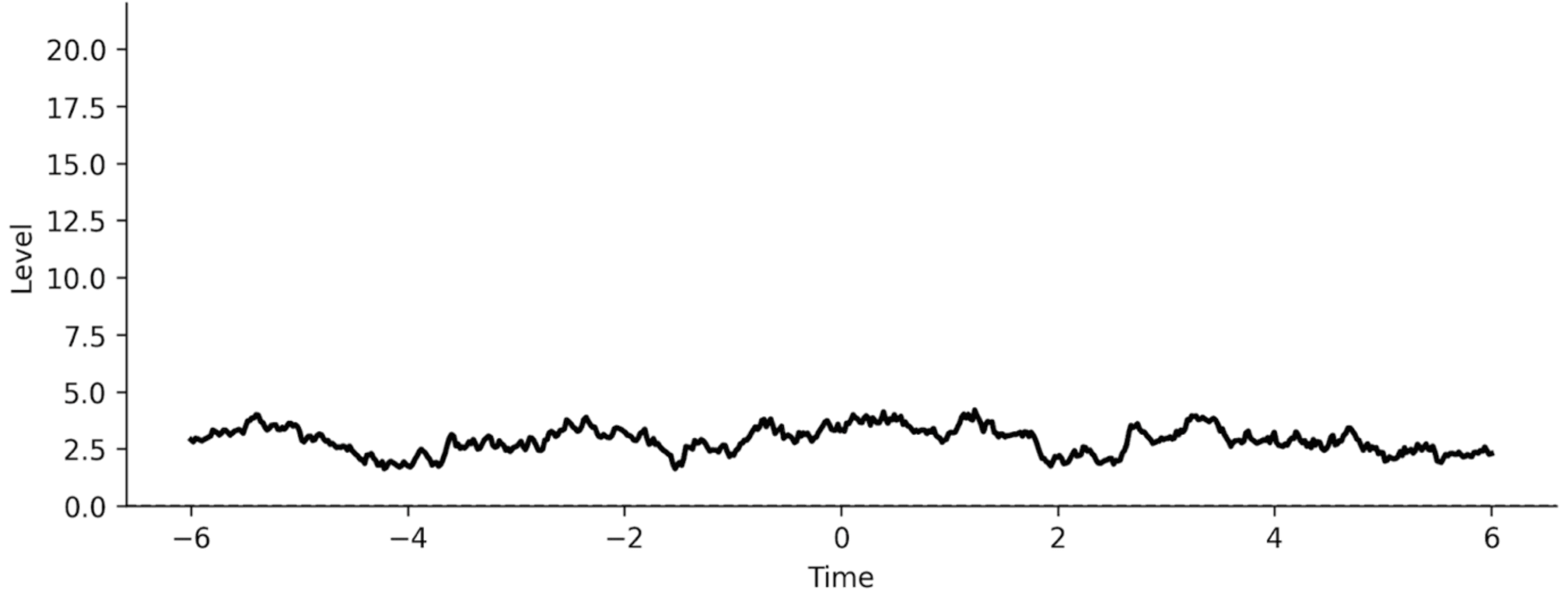

Of course this is all very idealized. Because circadian rhythms are also biological rhythms and biology is horrible, there’s no guarantee that they’ll look anything like this. I invite you to come up with a single definition of mesor for this guy:

But at the very least you can often come up with a notion of amplitude that makes sense, and this often aligns with what people want circadian health to be.

Want to feel more alert during the middle of the day? Sounds like amplitude. Want to sleep deeper at night? Yep, amplitude. Want to efficiently metabolize food during waking hours (and turn off that system at night)? Amplitude. It’s all about having your systems set to GO during the day and RECOVER at night.

Amplitude is set by the clarity and regularity of your day-night signal. It’s about what you do over the full 24-hour day, not just the fringes of it. Bright days/dark nights (Click Here), time-restricted eating (Click Here)—these are amplitude interventions.

There’s only one problem. Amplitude is really, really hard to measure.

You might notice that I’m being very vibes-y in the above about which rhythm, exactly, I’m talking about boosting the amplitude of. And this is the problem. There’s the core pacemaker in your brain, which is hard to reach and measure without you being dead, at which point you’ve probably got more pressing concerns. There are easier-to-get-at rhythms all throughout your body, but most of them are layered under lots of other rhythms that don’t have anything to do with circadian rhythms and can mangle the signal—think: food, activity, emotions.

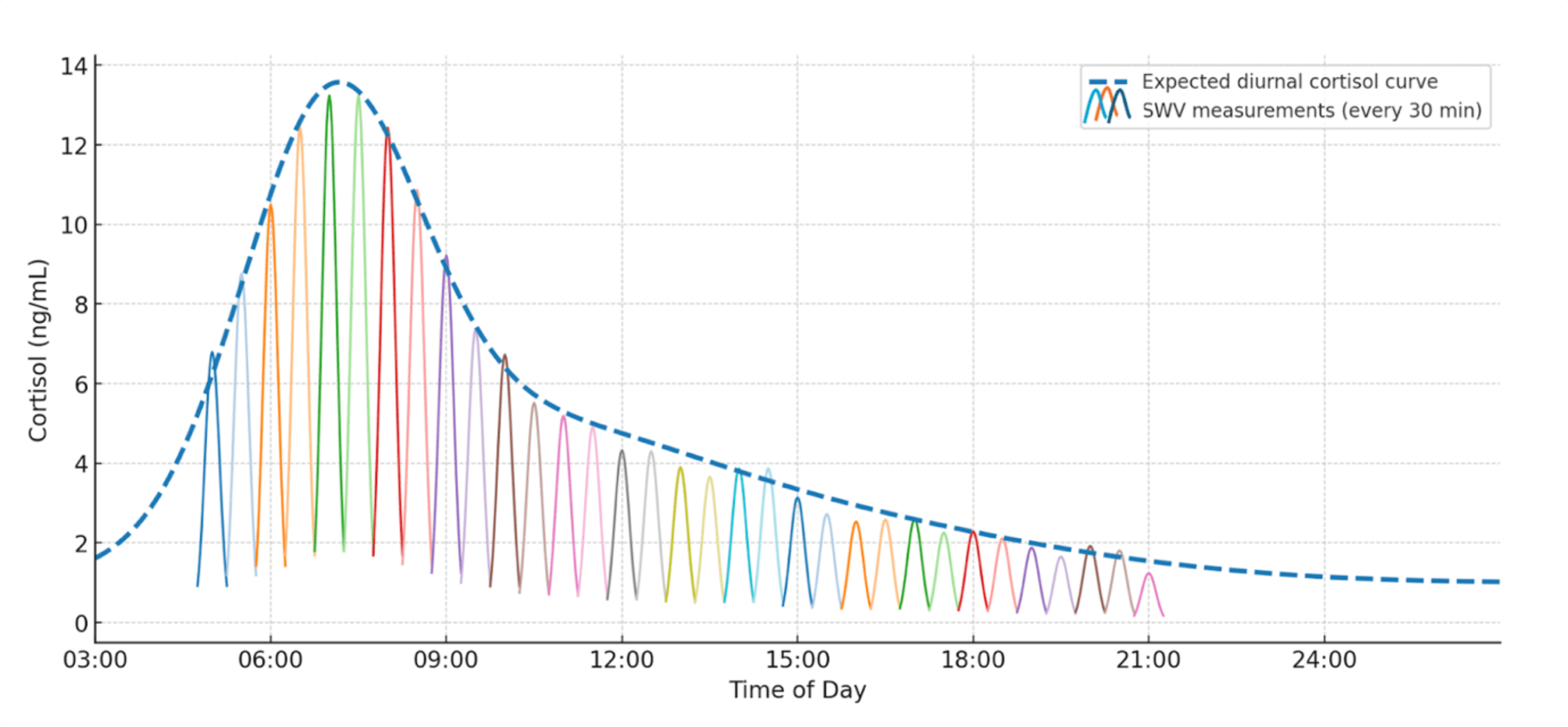

We usually use melatonin rhythms (i.e., the circadian hormone for darkness) as our gold standard circadian biomarker, which work quite well for determining what someone’s phase is after only 5-6 hours of providing a saliva sample every 30 minutes. But if you want to pick up amplitude from a melatonin rhythm, you’re looking at having them spit into tubes for a full day, in the dark, without sleeping. This is somewhat hard to convince your average person off the street to do.

Oh, and by the way: Some people just naturally produce a TON of melatonin, for reasons that are probably unrelated to their underlying circadian rhythm. You can think of it like this:

So if you really want to get at amplitude, you need to look at the same person across multiple days. Now we’re up to a minimum of 48 hours of spitting into tubes in the dark. This is an even harder sell.

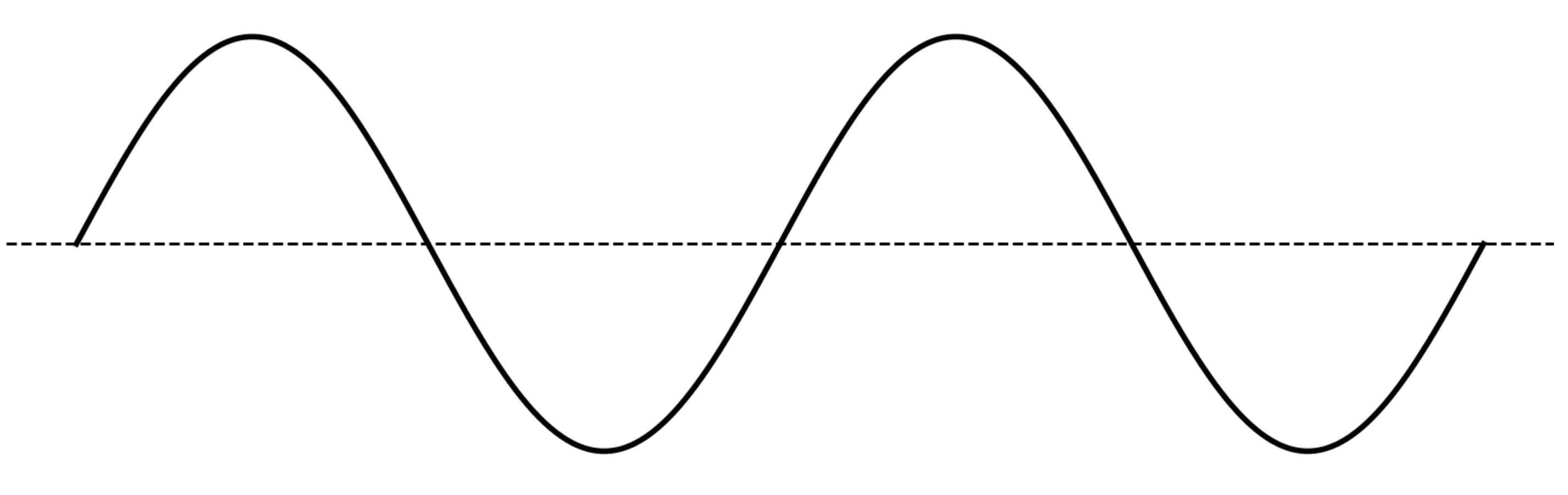

But amplitude really does seem to be the problem with the shift workers I talk to—and the same goes for anyone like them, who feels like their rhythm has lost its groove. A healthy melatonin rhythm should look something like this:

But I’ve seen disrupted melatonin rhythms that look basically like this:

This, to me, is can fall asleep whenever, can’t stay asleep for long, in graph form.

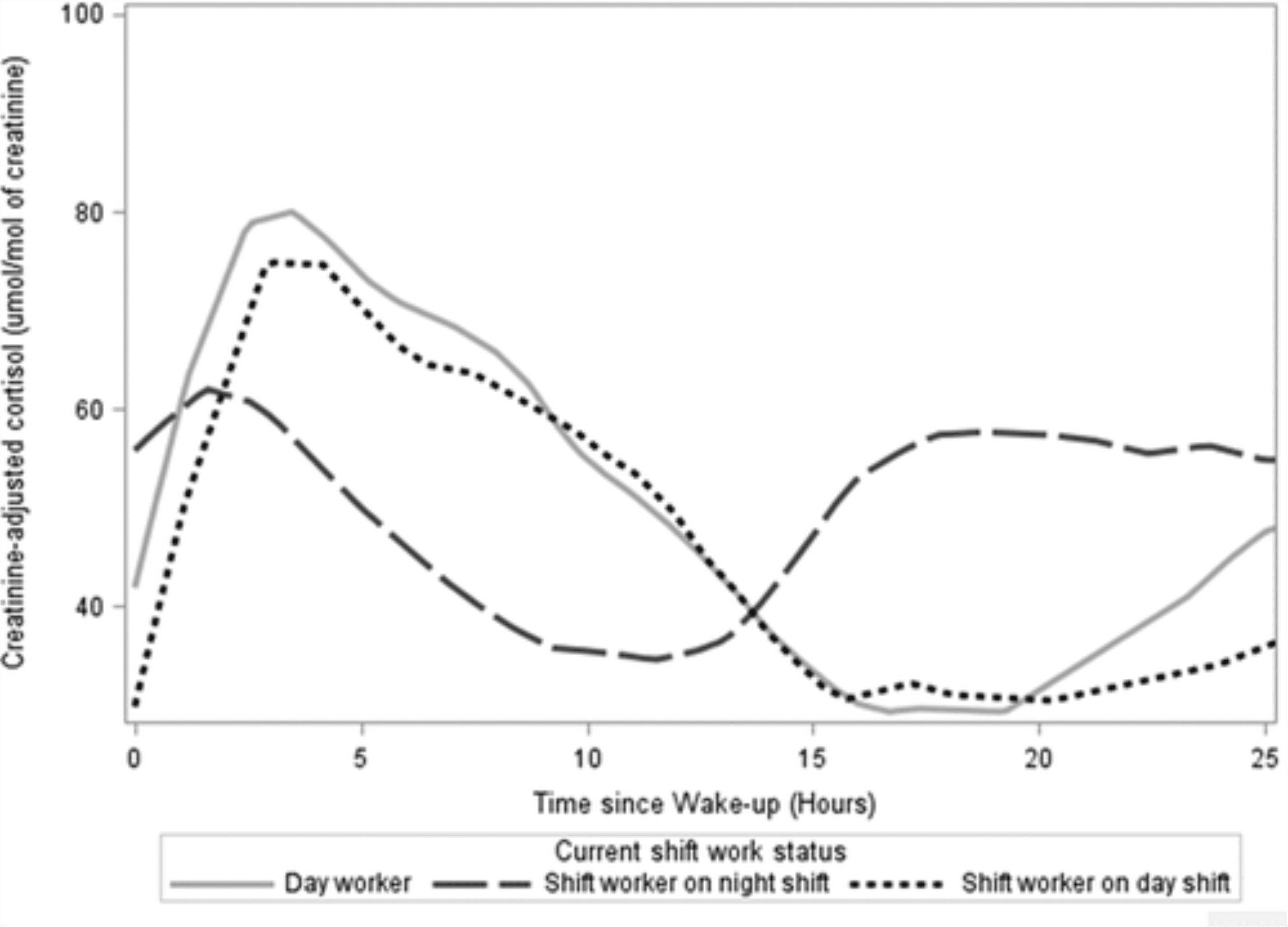

Of course, it’s not just melatonin. Cortisol, a critical hormone for inflammation, glucose regulation, blood pressure, you name it, also has a circadian rhythm and this notion of amplitude.

We know that real shift workers working nights out in the real world tend to have flatter, shifted cortisol rhythms with lower highs and higher lows:

Hung, E.W. et al. (2016) ‘Shift work parameters and disruption of diurnal cortisol production in female hospital employees’, Chronobiology International, 33(8), pp. 1045–1055. doi:10.1080/07420528.2016.1196695.

And it’s not hard to imagine how a low amplitude rhythm, showing up as a chronic level of elevated cortisol across the full 24-day, could cause health problems. It’s like running your car all day and night instead of ever taking the keys out of the ignition when you park. You’re putting constant wear and tear on the system: stress that adds up, day in and day out, until something finally gives.

I want to be able to put an exact number to the cost of that wear and tear—X% greater risk of heart disease from Y years spent idling in a low amplitude state; Z% greater risk of metabolic disease—but we’re hamstrung by the challenge of measurement here. There’s a whole set of questions that are ripe for answering around circadian amplitude, cortisol response, and the ramifications for health. We just need a way to see amplitude (in the same person, across many days) that we don’t have right now.

Please excuse me as I hand the mic to my friends at Lume.

When Olivia talks about amplitude as “the rhythm losing its groove,” it resonates deeply with what we’ve been seeing at Lume. Cortisol amplitude, in particular, is one of the clearest indicators of how well the internal clock is functioning. A strong rise in the morning followed by a deep recovery at night aligns closely with the lived experience of good health, stable mood, and sustained energy in our users. The challenge is that, despite its importance, this rhythm has been nearly impossible to observe directly.

All the tools we’ve had for decades give us only a single snapshot. A blood draw here. A saliva sample there. Trying to understand a 24-hour rhythm from these freeze-frame moments is like trying to understand a movie from a screenshot. You can argue endlessly about the plot because you never saw the whole thing.

And this is why amplitude has been stuck in the realm of “we know it matters, but we can’t measure it without ruining someone’s week.”

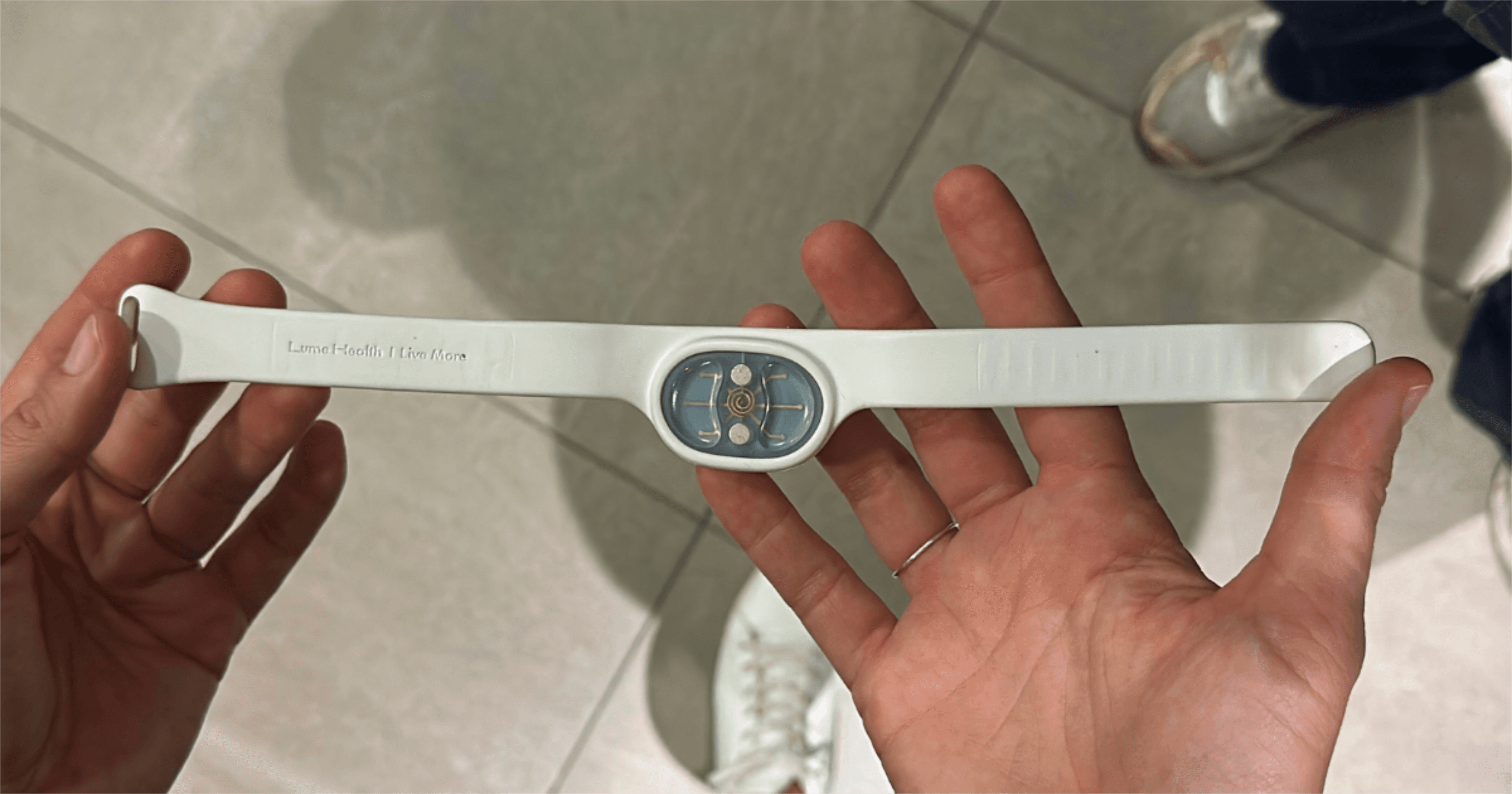

So that’s where we’ve been focusing our effort. At Lume Health, we’ve been building a wearable sensor that lets us measure cortisol continuously and non-invasively- through the skin. No tubes, no clinic visits, no asking people to sit in the dark for 48 hours. Instead, our device gently generates micro-amounts of sweat and uses aptamers (little strands of DNA that act like molecular detectives) to pick up cortisol as it fluctuates in real time.

When cortisol binds to its aptamer, the sensor shifts its electrical signal. Those shifts—tiny, fast, constant, become the curve. Your curve. A direct look at how your rhythm rises, falls, and responds to life as it unfolds.

For the first time, we’re able to see something that, until now, we’ve only been able to infer: the full shape of someone’s circadian rhythms. The phase. The amplitude. And once you can see that rhythm, you can understand it. You can intervene on it. You can strengthen it.

This is just the beginning. Once amplitude becomes measurable in daily life, not once a decade in a sleep lab, but every day on your wrist, we can finally start answering the questions circadian scientists have been circling for years.

Heart-rate monitors made invisible cardiovascular signals part of everyday living. Continuous glucose monitors transformed metabolic awareness. Continuous hormone monitoring will do the same for circadian health: bringing amplitude out of the shadows so we can finally understand and strengthen the rhythms that govern so much of how we feel.

Jonathan Moustakis

MD, CTO of Lume Health